NOAA has issued a El Niño watch for the remainder of 2014

ENSO Alert System Status: El Niño Watch

Synopsis: The chance of El Niño is about 70% during the Northern Hemisphere summer and is close to 80% during the fall and early winter.

During June 2014, above-average sea surface temperatures (SST) were most prominent in the eastern equatorial Pacific, with weakening evident near the International Date Line (Fig. 1). This weakening was reflected in a decrease to +0.3oC in the Niño-4 index (Fig. 2). The Niño-3.4 index remained around +0.5oC throughout the month, while the easternmost Niño-3 and Niño-1+2 indices are +1.0oC or greater. Subsurface heat content anomalies (averaged between 180o-100oW) have decreased substantially since late March 2014 and are now near average (Fig. 3). However, above-average subsurface temperatures remain prevalent near the surface (down to 100m depth) in the eastern half of the Pacific (Fig. 4). The upper-level and low-level winds over the tropical Pacific remained near average, except for low-level westerly anomalies over the eastern Pacific. Convection was enhanced near and just west of the Date Line and over portions of Indonesia (Fig. 5). Still, the lack of a clear and consistent atmospheric response to the positive SSTs indicates ENSO-neutral.

Over the last month, no significant change was evident in the model forecasts of ENSO, with the majority of models indicating El Niño onset within June-August and continuing into early 2015 (Fig. 6). The chance of a strong El Niño is not favored in any of the ensemble averages for Niño-3.4. At this time, the forecasters anticipate El Niño will peak at weak-to-moderate strength during the late fall and early winter (3-month values of the Niño-3.4 index between 0.5oC and 1.4oC). The chance of El Niño is about 70% during the Northern Hemisphere summer and is close to 80% during the fall and early winter (click CPC/IRI consensus forecast for the chance of each outcome).

Aug 7th update: ENSO Alert System Status: El Niño Watch

Synopsis: The chance of El Niño has decreased to about 65% during the Northern Hemisphere fall and early winter.

During July 2014, above-average sea surface temperatures (SST) continued in the far eastern equatorial Pacific, but near average SSTs prevailed in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1). Most of the Niño indices decreased toward the end of the month with values of +0.3oC in Niño-4, -0.1C in Niño-3.4, +0.2oC in Niño-3, and +0.6oC in Niño-1+2 (Fig. 2). Subsurface heat content anomalies (averaged between 180o-100oW) continued to decrease and are slightly below average (Fig. 3). The above-average subsurface temperatures that were observed near the surface during June (down to 100m depth) are now limited to a thin layer in the top 50m, underlain by mainly below-average temperatures (Fig. 4). The low-level winds over the tropical Pacific remained near average during July, but westerly wind anomalies appeared in the central and eastern part of the basin toward the end of the month. Upper-level winds remained generally near average and convection was enhanced mainly just north of the equator in the western Pacific (Fig. 5). The lack of a coherent atmospheric El Niño pattern, and a return to near-average SSTs in the central Pacific, indicate ENSO-neutral.

Over the last month, model forecasts have slightly delayed the El Niño onset, with most models now indicating the onset during July-September, with the event continuing into early 2015 (Fig. 6). A strong El Niño is not favored in any of the ensemble averages, and slightly more models call for a weak event rather than a moderate event. At this time, the consensus of forecasters expects El Niño to emerge during August-October and to peak at weak strength during the late fall and early winter (3-month values of the Niño-3.4 index between 0.5oC and 0.9oC). The chance of El Niño has decreased to about 65% during the Northern Hemisphere fall and early winter (click CPC/IRI consensus forecast for the chance of each outcome).

This discussion is a consolidated effort of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NOAA’s National Weather Service, and their funded institutions. Oceanic and atmospheric conditions are updated weekly on the Climate Prediction Center web site (El Niño/La Niña Current Conditions and Expert Discussions)

Q: What is El Niño?

A: El Niño is the Peruvian name given to an abnormal warming of the oceans around Christmastime off the west coast of South America. Since this colloquial naming occurred, scientists have defined exactly what El Niño means to them: A warming of the ocean of more then 0.5 degrees Celsius (about one degree Fahrenheit) for three consecutive months in an area along the equator from the west coast of South America west toward the central Pacific Ocean. That’s a handful of a definition, so just think of it as a warming of the central Pacific Ocean.

Q: What does El Niño mean to skiers?

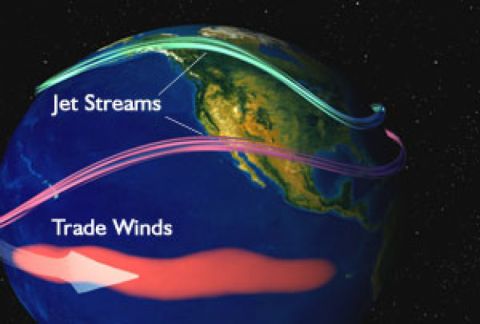

A: Skiers care about El Niño because a significant change in water temperature across a large area of the ocean affects weather patterns across the globe. Since the strength of El Niño peaks during the Northern Hemisphere’s fall, winter and early spring, El Niño’s effects on weather also peak during winter. Some of these include droughts across Australia, heavy rain over Peru and a change in the jet stream across North America, which influences the location of the heaviest snow.

For the U.S., El Niño causes a more southerly storm track, which often brings higher than average snowfall to the southern third of the U.S. and less snow with warmer temperatures across the northern third of the U.S. This frequently means that Southern California, Arizona, New Mexico and sometimes southern Utah and Colorado can see increased snowfall in El Niño years. There can also be cooler-than-normal weather across the southeastern U.S., which can help ski areas in Georgia, Alabama and North Carolina with their snowmaking. If things come together just right, some storms can track up the East Coast and bring good amounts of snow to eastern areas of the Mid-Atlantic and New England.

Q: Are El Niño’s effects predictable?

A: El Niño always comes in slightly different shades. We usually see an El Niño every couple of years, but its strength changes each time and so does its effects on worldwide weather. El Niño is not the only climate phenomenon that can influence weather across the globe, so just looking at El Niño will rarely allow meteorologists to accurately predict snowfall for the season ahead.

That said, keep an eye on what scientists are predicting for El Niño and remember that it often means more snow across the southern third of the U.S., but also remember that each snowstorm has a mind of its own and you’ll be far better served looking for snow on the five-day forecast than betting on a three to six-month snow forecast based on Chris Farley’s "the Niño."