'Super' El Niño for 2014/15 Ski Season?

Forecasters with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have issued an El Nino Watch for 2014, meaning that there's a good chance we'll see this enigmatic weather pattern return after a roughly four-year hiatus.

However, with news stories reporting on a potential warm winter to come for North America, along with talk of a possible 'super' El Nino, like we saw back in 1997-1998, or even an 'epic' or 'monster' El Nino unlike we've ever seen, what exactly does all this mean?

What is El Nino, how does it form and what's behind the current forecasts? What does it mean for Canada if it does form, and are reports succumbing to hyperbole?

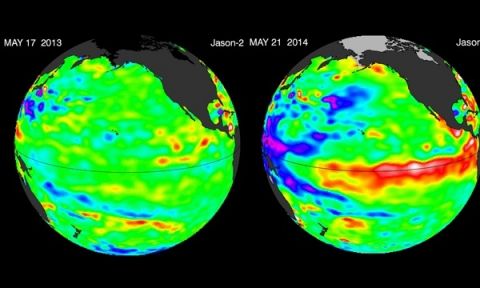

Global sea surface temperature in May 2013 and May 2014. Photograph: NASA

The Jason-2 satellite sees something brewing in the Pacific, researchers say it could be a significant El Niño with implications for global weather and climate.

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that occurs when a vast pool of water in the western tropical Pacific Ocean becomes abnormally warm. Under normal conditions, the warm water and the rains it drives are in the eastern Pacific.

El Niño occurs every few years. Its most direct impacts are droughts in normally damp places in the western Pacific, such as parts of Indonesia and Australia, while normally drier places like the west coast of South America suffer floods. But the changes affect the global atmospheric circulation and can weaken the Indian monsoon and bring rains to the western US.

It is not certain what tips the unstable Pacific Ocean-atmosphere system into El Niño, but a weakening of the normal trade winds that blow westwards is a key symptom. In 2014, the trigger may have been a big cluster of very strong thunderstorms over Indonesia in the early part of the year, according to Dr Nick Klingaman from the University of Reading in the UK.

An El Niño is officially declared if the temperature of the western tropical Pacific rises 0.5C above the long-term average. The extreme El Niño year of 1997-98 saw a rise of more than 3C.

El Niño is one extreme in a natural cycle, with the opposite extreme called La Niña. The effect of climate change on the cycle is not yet understood, though some scientists think El Niño will become more common.

The global El Niño weather phenomenon, whose impacts cause global famines, floods – and even wars – now has a 90% chance of striking this year, according to the latest forecast released to the Guardian.

El Niño begins as a giant pool of warm water swelling in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, that sets off a chain reaction of weather events around the world – some devastating and some beneficial.

India is expected to be the first to suffer, with weaker monsoon rains undermining the nation’s fragile food supply, followed by further scorching droughts in Australia and collapsing fisheries off South America. But some regions could benefit, in particular the US, where El Niño is seen as the “great wet hope” whose rains could break the searing drought in the west.

The knock-on effects can have impacts even more widely, from cutting global gold prices to making England’s World Cup footballers sweat a little more.

The latest El Niño prediction comes from the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which is considered one the most reliable of the 15 or so prediction centres around the world. “It is very much odds-on for an event,” said Tim Stockdale, principal scientist at ECMWF, who said 90% of their scenarios now deliver an El Niño. "The amount of warm water in the Pacific is now significant, perhaps the biggest since the 1997-98 event.” That El Niño was the biggest in a century, producing the hottest year on record at the time and major global impacts, including a mass die-off of corals.

“But what is very much unknowable at this stage is whether this year’s El Niño will be a small event, a moderate event – that’s most likely – or a really major event,” said Stockdale, adding the picture will become clearer in the next month or two. “It is which way the winds blow that determines what happens next and there is always a random element to the winds.”

The movement of hot, rain-bringing water to the eastern Pacific ramps up the risk of downpours in the nations flanking that side of the great ocean, while the normally damp western flank dries out. Governments, commodity traders, insurers and aid groups like the Red Cross and World Food Programme all monitor developments closely and water conservation and food stockpiling is already underway in some countries.

Professor Axel Timmermann, an oceanographer at the University of Hawaii, argues that a major El Niño is more likely than not, because of the specific pattern of winds and warm water being seen in the Pacific. “In the past, such alignments have always triggered strong El Niño events,” he said.

El Niño events occur every five years or so and peak in December, but the first, and potentially greatest, human impacts are felt in India. The reliance of its 1 billion-strong population on the monsoon, which usually sweeps up over the southern tip of the sub-continent around 1 June, has led its monitoring to be dubbed “the most important weather forecast in the world”. This year, it is has already got off to a delayed start, with the first week’s rains 40% below average.